I thought of Joe Resnick, a sportswriter who resigned himself to dying alone when he got cancer in 2016. He didn't think he was a big enough deal that people should notice.

People noticed.

I heard from friends from college who I hadn't heard from in 43 years. One -- our mutual best friend back in the day -- called Joe to read him the column.

About a week later, Joe died, leaving behind a world that still remembers him.

(Originally published November 11, 2016)

I haven't seen this guy since 1976, the day we graduated from Emerson College in Boston.

He's Joe Resnick, a kid from Brooklyn and, like most of us who palled around together at Emerson, he wanted to be a broadcaster or sportswriter and a fair number of us went on to do just that.

It was a relatively small crew of would-be journalists who were big sports fans at the school. We played Strat-O-Matic, went to Red Sox games at Fenway Park and played street hockey in the dorm or apartment -- Joe was a New York Rangers fan, as I recall, for it seemed he always had a Rangers jersey on , before wearing hockey jerseys was cool -- and we practiced our writing and learned not to be afraid of microphones and which camera to look into at a campus radio station or TV station that nobody watched or listened to, and eventually we graduated and went our separate ways.

Some of us kept in touch; some of us didn't. There was a future to get on with. There'd always be time for the past some other time in the future.

I'd heard over the years that Joe went off to the Associated Press and was writing about sports.

I'm at the time of my life where, more often than not, I learn what happened to some of those old classmates when I hear that they've died or are dying.

Joe, who became a bigshot in the sports writing world as a freelancer, is dying.

I learned whatever happened to him in a wonderful tribute to him today in the Los Angeles Times, which noted that millions of you have read his words, but few recognized him. His byline rarely appeared, another reason why a lot of people never knew whatever happened to him.

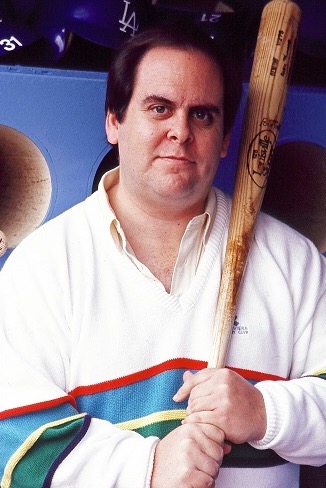

He's got Stage IV colon cancer now and when I read the story in the Times and looked at the picture, I had no idea I was looking at that Joe Resnick -- my Joe Resnick.

Until I looked at his eyes. When the rest of us withers, our eyes always stay the same. Joe's eyes always had a sadness to them with just the right amount of mischief.

He stopped showing up at the ballpark and he resigned himself to die alone in his apartment, apparently believing that people had forgotten him. He'd lost 100 pounds. He was too weak to answer the door when some people stopped by, Los Angeles Times columnist Bill Plaschke writes today. It was a small group of sportswriters, photographers, and other journalists.

They learned he was crushed by medical bills, and so they set up a GoFundMe page to help.

The anonymous sportswriter thought nobody was watching, but it turns out everybody was watching, admiring his work ethic, marveling at his persistence. The man with no byline had indelibly etched his name in the minds of those who watched him carve a lifetime out of simply showing up and doing his job.Every office has a Joe Resnick, Plaschke writes.

The fund’s goal was $20,000 and it reached that figure in a few days, with contributions from sports executives to players to countless journalists. Donations ranged from $10 to $1,000. Love showed up in everything from personal calls from Vin Scully and Mike Scioscia and a voicemail from Doc Rivers, to countless texts from other sports figures. The fund is now at $22,250 and growing.

“He was taken aback, he had no idea people cared so much about him,” said Shepler. “He would go through the list of contributors every day not to see the money, but to see the names, he couldn’t believe so many people remembered.”

Dilbeck and Times staffer Dylan Hernandez came up with the idea of giving Resnick the BBWAA’s annual Bob Hunter Award for meritorious coverage even though he wasn’t a member. Within hours, the 50-person membership approved the honor. Within days, the plaque was engraved, and last week, 11 of Resnick’s friends surprised him with an impromptu ceremony around the hospital bed in the middle of his living room, where he is receiving hospice care.

The moment Resnick saw the plaque he began weeping. He held the thick wood memento close to his face and kissed it. He then pulled out an official BBWAA cap and jacket he had been saving all of his professional life, maybe just for this moment.

“Today is the first day I belong,” he whispered.

He began crying again, and soon everyone around him was red-eyed with the reminder that things many take for granted — a sense of permanence, a sense of place — were gifts to be honored and cherished. In opening eyes and hearts to these truths during his three decades in the shadows, the anonymous sportswriter had actually been writing the story of his career.

“This is the best day of my life,” Joe Resnick whispered, solitary no more, remembered forever.

"He’s the part-timer who shows up for work in an isolated corner desk every day, occasionally gruff, sometimes grumpy, but always there. He arrives earlier than the boss who barely knows him, stays later than the summer interns who are paid more, has statistics on everything and everybody. He’s the employee everyone actually thinks is full time until he admits he doesn't have insurance," he said.

He's the guy we let slip into the past and wonder whatever became of. He's the guy who makes us ashamed that we'd failed to be the friends we said we were.

He's the guy who reminds us that we can always be better people than we presently think we are.

Update: Joe died about 9 days after I wrote this.